A trip to East Java

Watu Karung, Blitar and Malang

I have just got back from a trip to East Java. I travelled there with a Swiss friend I have got to know in Yogyakarta, where I am currently based. He has lived in Indonesia for decades and owns a campervan, which is what we used to get there.

Our first destination was Watu Karung, a small village on the sea in Pacitan Regency, on the southern coast of Java. It is a 4-hour drive from Yogyakarta. I quite enjoyed spending a few days there. The village is small and peaceful, hemmed in on three sides by green mountains, but it has a number of guesthouses and restaurants for visitors. During the weekends it gets busier, but when we arrived, on a Thursday, it was extremely quiet. I had the second floor of my guesthouse entirely to myself (my travel partner slept in his camper next to the beach).

Watu Karung has a sandy beach, and just in front of it there is a row of small family-owned restaurants facing the sea. On weekdays most of them are closed, but when we arrived the only restaurant that was open cooked us some delicious fresh fish with vegetables and rice, for the equivalent of 4 euros between the two of us.

The sea at Watu Karung is very rough, typically for the South Coast of Java, to the point that doing anything more than wading in the water could be quite dangerous. This is part of the reason why Java’s major seaports and cities, from Surabaya to Semarang to Jakarta, are all on the north coast. The big waves are great for experienced surfers however, and we met a foreign couple who had come there to surf, an Australian and a Californian (of course).

We stayed in Watu Karung for three nights. Although it was the rainy season we were blessed with good weather, and it only poured briefly every afternoon. On Saturday the village got much busier, with plenty of visitors from cities like Malang and Yogyakarta. On the beach there were throngs of people taking photos, although, typically for Java, no one was wearing a bathing suit. The women waded into the sea fully clothed, many of them wearing hijabs. Apparently you used to see women in bathing suits on Javanese beaches 30 years ago, but nowadays, due to Indonesia’s Islamisation, it has come to seem inappropriate.

The following day we drove on to Blitar, a town in East Java notable for being the place where Indonesia’s first president and national hero Sukarno is buried. His mausoleum is now a place of pilgrimage. Sukarno was not from Blitar, and he died in Bogor, near Jakarta, in 1970 after being placed under house arrest by the regime of Suharto, who had overthrown him three years previously. Sukarno wanted to be buried in Bogor, but Suharto didn’t want his grave to be located so close to Jakarta, where it could become a fulcrum for opposition to his rule.

Instead Sukarno was buried in Blitar, next to his mother’s grave, against the wishes of his family. In 1979, after Sukarno’s legacy was rehabilitated, the regime built a mausoleum at the site of his grave. The family still opposed this, but the grave quickly became a place of pilgrimage. After the fall of Suharto, the city of Blitar started to make full use of Sukarno’s name to promote tourism.

The site now attracts tourists and politicians, but also large numbers of spiritual pilgrims. There is a strong tradition of venerating dead “holy men” among the Javanese, and every year dozens of thousands of mostly Muslim Javanese visit Sukarno’s grave to obtain his spiritual blessings.

When we arrived the site was full of large groups of visitors, most of whom looked like devout Muslims. We were the only bule (white Westerners) in sight. Various shy teenagers asked if they could take photos with us. After agreeing a couple of times, we started politely refusing so that we wouldn’t spend all day taking photos with strangers.

Entry to the mausoleum was free. There was a large Javanese-style pavilion above the graves of Sukarno and his parents. The stone slab on his grave said “Bung Karno” (comrade/brother Karno), as he is popularly known. Like many Indonesians, Sukarno went by a single name.

The pavilion was packed with women in veils and men in traditional Javanese clothing, chanting and praying as they sat on the floor. Sukarno himself was born of a Javanese Muslim father and a Hindu Balinese mother. He was a Muslim but there is no evidence he was particularly religious. He was more of a nationalist who was enthusiastic about the non-aligned movement, pancasila and Indonesian-style socialism. He imagined Indonesia as a secular and multi-religious nation. All the same, his mausoleum now has a distinctly Islamic feel to it.

In order to leave the site, visitors were required to make their way at an exhaustingly slow pace through a corridor packed with people and full of souvenir stands on both sides. Rather than do that we walked back out through the entrance, pretending not to understand the sign in Indonesian that said “no exit”. The guards made no attempt to stop us. Sometimes being a bule has its advantages.

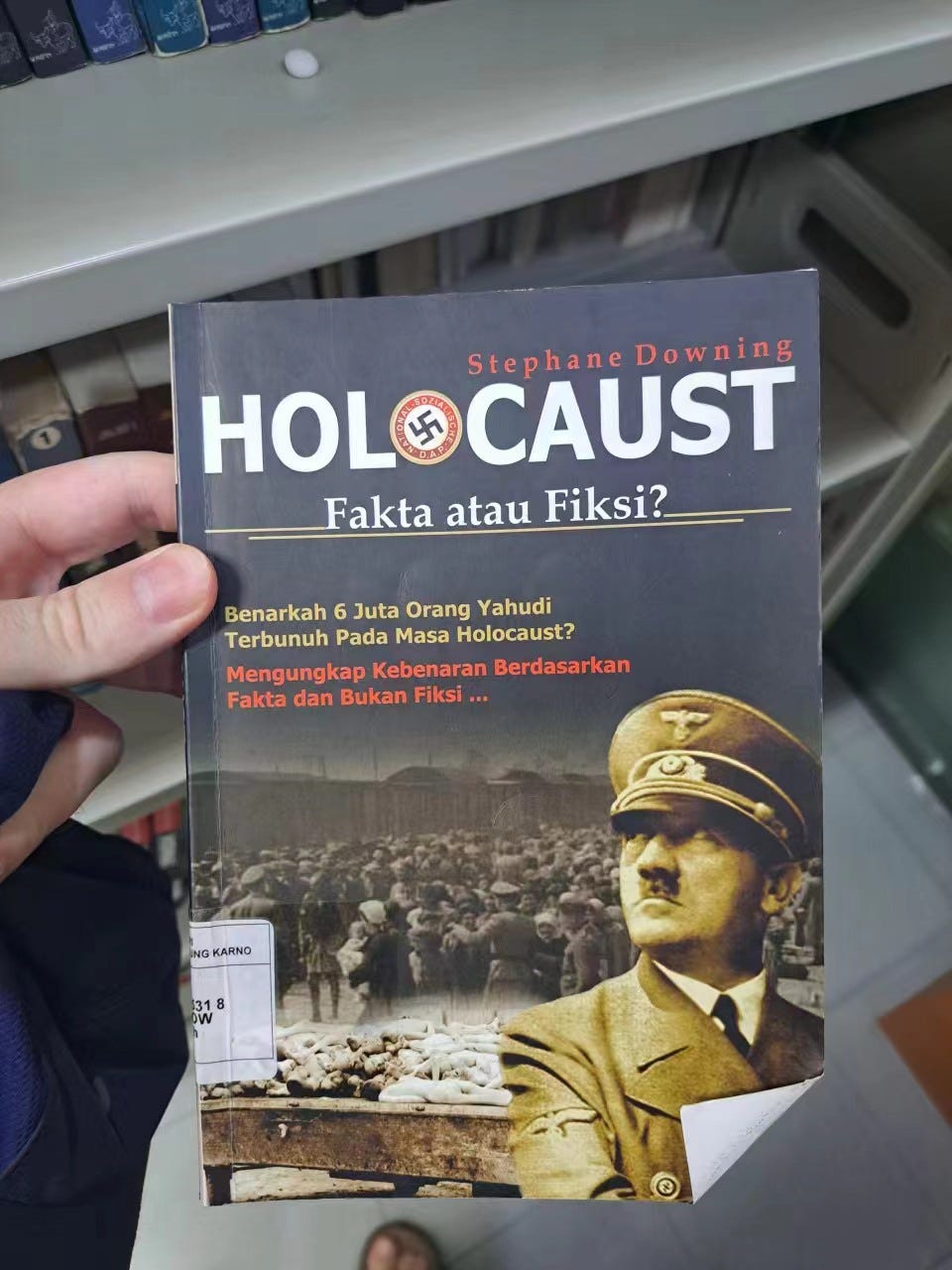

Outside of the entrance there are large murals, depicting scenes from Sukarno’s life. There is also a library which was built in 2004. We went into the library, which has books in Indonesian on all kinds of topics. Browsing the books, I got a nasty surprise when I reached the section on World War II: there were a couple of books by a holocaust denier translated into Indonesian, ironically placed right next to the Diary of Anne Frank. One of them was called “the Holocaust: fact or fiction?”.

The books were authored by one Stephane Downing, of whose existence I can find no independent confirmation. All the Google entries on him are in Indonesian. Perhaps he is just a figment of someone’s imagination, and the books were actually written by Indonesians rather than translated. On another bookshelf, I found the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in Indonesian. While it is sadly common to see antisemitic books of this sort for sale in Arab countries, it is the first time I encountered this in Indonesia, and it left an extremely bad taste in my mouth.

In keeping with this theme, in a street near the mausoleum we saw a banner with a bizarre quote by Sukarno, which could be translated as follows: “if you are Hindu, don’t become Indian; If you are Muslim, don’t become an Arab; if you are Christian, don’t become a Jew; but rather remain an Indonesian, with the rich cultural traditions of this archipelago.”

The point of the quote is clearly to encourage everyone to be proud Indonesians, regardless of their religion. But the part on “not becoming Jewish” if you are a Christian points to a complete misunderstanding of the relationship between Judaism and Christianity. I have previously heard Indonesian Christians tell me that local Muslims have trouble telling Judaism and Christianity apart, and this seemed to confirm it.

That night I stayed in the Tugu Hotel, a historic hotel in the centre of Blitar. While my room wasn’t luxurious, the old colonial-style ambience was pleasant, and the price was reasonable (26 euros). After dinner I walked around a bit. Blitar seemed like a fairly nondescript provincial city.

The next day we drove on to Malang, the second biggest city in East Java after the huge port of Surabaya. Malang has a reputation as a cultural and educational centre and a nice place to visit. It has a mild climate due to being located on a plateau, and under Dutch colonialism it was a popular destination for European residents. The city has a history tracing back to the 13th century, when it was the capital of the Hindu-Buddhist Singhasari Kingdom.

I found Malang to be one of the pleasantest Indonesian cities I’ve visited. It is surrounded on all sides by volcanoes, making for some pretty nice views (although I was there during the rainy season, when clouds often hide the view). The city centre is fairly walkable, unusually for Indonesia, and it has some historical heritage. The long, attractive Idjen Boulevard is lined with well-tended bougainvillea against a backdrop of old colonial villas, now probably inhabited by politicians and successful business people.

Walking around, I came across the “Kajoetangan Heritage Village”, a traditional neighbourhood located in the heart of the city. If you aren’t a local resident you have to pay a ticket to enter the maze of alleys from the main road, at a cost of 10,000 Rupiah if you are a foreigner or 5,000 if you are an Indonesian citizen (0,6 and 0,3 Euros). The narrow alleys have well preserved Dutch colonial houses, cafes and a village-like atmosphere, with local children running around freely.

I also visited Malang’s bird market. Birds are a common pet in Java. There are mammals and reptiles on sale at the market as well, but birds are the most common merchandise and give the place its name. Unfortunately many of the birds shared packed cages and seemed to live in rough condition. We even saw a few owls on sale.

Another place we visited was the Tugu hotel, the fancier and more magnificent cousin of the one where I stayed in Blitar. The old hotel has become a tourist attraction in its own right, due to the huge collection of Javanese, Chinese and other Asian antiquities on display in its lavish and almost endless interiors. Some of the antiquities were stored in rooms where the lights were off and no one normally sets foot.

The following day we drove up to Batu, a town around 20 kilometres to the Northwest of Malang, further up in the hills. It is known as a resort town due to its cool weather and pleasant surroundings. It is best visited during the dry season, however. Since we were there during the rainy season it got positively chilly at night, while the views were hidden by clouds and the hikes were impractical due to the rain.

A few days later I parted ways with my travel partner, and I went back to Yogyakarta by train from Malang. Java is the only Indonesian island with a decent train network, and the 5.5 hour ride was quite comfortable. It had been nice to see more of Java, although I would really recommend travelling there during the dry season.