I am writing these words from Borneo.

Borneo is a massive island, the world’s third largest, divided between three different countries and cut almost exactly in half by the equator. It’s almost four times the size of Great Britain, but has less than a third of its population. Until recently much of it was covered in impenetrable rainforest, although unfortunately extensive logging is changing that.

The initial aim of my trip to Borneo was to visit Brunei, the smallest and least visited country in the region. Brunei is not very well connected however, so I first flew to Kota Kinabalu, the coastal capital of the Malaysian state of Sabah, in the island’s northern tip.

I spent my first two nights in a resort up on the hills overlooking the city. It was pleasant to be surrounded by lush tropical vegetation and fresh mountain air, and the views of the city and the sea from my balcony were quite something. On the other hand the fairly cheap resort, which clearly catered to a local crowd, was far from luxurious. It was also isolated and hard to leave, and the food in the restaurant was rather low-quality.

After two nights in the resort, I went down to the city to spend a final night there before taking the bus to Brunei. Kota Kinabalu is a relatively small city, with around half a million people, and it has a provincial feel. Like Malaysia in general, it seemed pleasant and relatively well-developed but also somewhat… uneventful, one could say.

Compared to Indonesia, on the other hand, everything felt a bit less chaotic and better run. After spending time in Indonesian cities, it was like a breath of fresh air to be in an urban setting that is actually walkable, with usable sidewalks, few scooters, and zebra crossings where they are needed. The local dining options were also quite cosmopolitan. I even found an extremely good and authentic Italian restaurant just around the corner from my hotel.

Just like most Malaysian cities, Kota Kinabalu has a strong Chinese element. There are plenty of people speaking to each other in Mandarin and other Chinese languages, and restaurants with authentic Chinese food. Signs seem to be equally divided between Chinese, English and Malay. I was surprised to read that only 20% of the city’s population is of Chinese ethnicity; I would have expected the figure to be higher.

Borneo’s links to China run deep: Chinese ships have been regularly visiting and trading with kingdoms in Northern Borneo since the first millennium AD. After breaking free of the Java-based Majapahit empire at the end of the 14th century, the kingdom of Brunei (which back then ruled the whole coast of Borneo, and even parts of what is now the Philippines) actually became a protectorate of China’s Ming Dynasty for a while.

Chinese have been settling in Borneo for over a thousand years, but most of the Chinese living in the area today descend from people who arrived during the era of European colonialism. They are currently a significant minority in all parts of the island, and there are few visible signs of friction between them and the Malay or other indigenous groups.

But under the surface all is not well, at least on the Malaysian side. Malaysia has enacted a dubious “affirmative action” policy for decades, favouring the bumiputera (“native” Malaysians) at the expense of the Chinese and Indian minorities. The clear purpose is to prevent the industrious Chinese (and to some extent the Indians) from dominating the economy.

Numerous places in university and government jobs are reserved for the bumiputera, and this angers the Chinese no end, judging by the complaints I’ve heard from Chinese Malaysians I’ve met in China over the years. In Sabah and Sarawak, the two states that make up Malaysian Borneo, the non-Chinese population is almost equally divided between Malays and various Dayak and other indigenous tribes. Both the Malays and the other indigenous groups are considered “native” Malaysians for the purpose of affirmative action policies. The Chinese are not.

Still, the casual visitor to Kota Kinabalu will notice no hint of these problems. The city does not seem to be divided into ethnic enclaves, the Chinese happily use Malay to communicate with other ethnic groups, and Muslim women in headscarves share the streets with Chinese women in shorts without any sign of tension. A political system that is only partly democratic keeps a lid on public debate, while Malaysia remains peaceful, having seen its last explosion of inter-ethnic violence all the way back in 1969.

After spending a night in a cheap hotel in the city centre, I woke up early to take the long-distance bus to Brunei. The journey takes about 9 hours. Surprisingly, you need to cross four borders along the way. The first border you cross is the one between the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak. This is an actual border, where you get a stamp in your passport on both sides.

Sabah and Sarawak maintain their own immigration regimes, distinct from Malaysia as a whole. Compatriots from peninsular Malaysia, where Kuala Lumpur is found and 80% of Malaysians live, are not allowed to stay in them for more than 3 months at a time without a valid reason. This is part of the autonomy that was granted the area so it would agree to join the Federation of Malaysia in the 60s.

After crossing into Sarawak we stopped for lunch in the nondescript town of Lawas, after which we entered Brunei, then re-entered Malaysia about 20 minutes later, and then finally re-entered Brunei for the last time. Tiny Brunei is actually divided in half by Malaysia. There’s now a bridge connecting the two sides, but we didn’t take that route. At every crossing we had to get off the bus, get our passports stamped to leave one country, get back on the bus, and then five minutes later get back off again and get stamped to officially enter another country.

Brunei

Finally we reached the Bruneian capital of Bandar Seri Begawan, usually just known as BSB. We were dumped at a bus station quite far out from the city centre. BSB is very different from most Southeast Asian cities. It’s not densely populated and buzzing with life. It’s more like a sprawling suburb, with low-rise blocks of flats and shopping complexes interspersed with patches of tropical nature.

There was a Canadian on my bus, the only other Westerner among the passengers. We both wanted to get to our hotels in the city centre, so we teamed up. There were no taxis in sight. In Brunei the cab-hailing app Grab, used in all other countries in the region, doesn’t work. The country has an app of its own, named Dart, which is the only one allowed. I downloaded it, but was unable to sign in.

I asked the driver of my bus, who pointed me towards a nearby market and said a taxi to the centre would cost 50 Brunei dollars (around 35 Euros). I had no Bruneian dollars, and for a short ride this seemed like a rip off. The Canadian agreed. Then a Chinese-looking man standing nearby, who had been chatting to the driver in Mandarin, turned to us and said he would give us a lift. The man turned out to be a Chinese-Bruneian who had studied in Glasgow and was very friendly. He drove us both to our respective hotels and wouldn’t take any payment.

The place where I stayed, Terrace Hotel, is an old hotel with old-fashioned decor that once hosted Lee Kuan Yew. While it’s far from luxurious, it is good value for money in relatively expensive Brunei, and it has a nice pool. It is also very central and in walking distance of BSB’s main sights.

While Brunei is expensive by Southeast Asian standards, I still found it to be far cheaper than Western Europe. The cost of my hotel, 37 Euro a night, would be unthinkable in the centre of a European capital. Food in night markets is around the same price as in Malaysia. It’s certainly possible to stay there a few days without spending a fortune.

People often get Brunei mixed up with the Gulf emirates, because it’s small, rich in oil, run by an absolute monarch and has strict Islamic laws. This is understandable, but in fact when you visit it feels quite different. The capital is not a city like Dubai or Doha, trying to impress the visitor with skyscrapers and glitzy malls. Even the city centre is quite low key, and mostly devoid of large, flashy buildings.

Brunei is undeniably wealthy. According to the IMF, its GDP per capita currently ranks 29th in the world, coming just after Italy and Cyprus, and before the Bahamas and Japan. Malaysia’s per capita GDP, 67th worldwide, is not much more than a third of Brunei’s. Measured at purchasing power parity Brunei’s per capita GDP is even higher, coming 10th in the world, just after the Netherlands and Denmark. Its wealth derives entirely from the export of oil and natural gas. The revenues, when divided by a population of just half a million, go a long way.

The city certainly felt orderly and well-run, with no scooters, street vendors or obviously poor people. It must also be said that many of the blocks of flats in the suburbs looked rather run down. A majority of Brunei’s population is ethnically Malay, although there are minorities from other Bornean ethnic groups, and around 10% are Chinese. There are also quite a few immigrants from Malaysia, Indonesia and South Asian countries, attracted by Brunei’s rich economy.

Where Brunei’s capital really tries to impress is in the construction of mosques. The most eye-catching building in the city centre is probably the huge Omar Ali Saifuddien Mosque, which can accommodate 3,000 worshippers. Named after Brunei’s 28th sultan, the father of the current one, the mosque was completed in 1958. The mosque was actually developed by Italian sculptor Rudolfo Nolli, and its floors and columns were made from Italian marble, paid by the oil money that was already flowing into the country. The building of the mosque inspired a novel by Anthony Burgess, who spent two years in Brunei.

Brunei distinguishes itself from its neighbours by its very public religiosity. Sunni Islam is the country’s official religion, which is also true in most of Malaysia, but in Brunei things are taken a step further. The country’s official name, Brunei Darussalam (“abode of peace” in Arabic), points to its Islamic character. The sale of alcohol is completely banned throughout the country, and there is no nightlife in the Western sense. Large signs on the highway and in public places quote the Quran in Arabic.

Brunei’s official language is Malay written in the Jawi script, an Arabic-based alphabet. In reality people most commonly use the Latin alphabet, which supplanted Jawi everywhere in the Malay-speaking world during European colonialism. Even so, official signs are all written in Arabic characters, contributing to lend Brunei a more “Islamic” atmosphere.

In 2014, the Bruneian government made international headlines by formally introducing Sharia Law. In theory, this means that penalties like death by stoning for adultery and homosexuality are now on the books. In fact, Brunei has had a de-facto moratorium on the death penalty since 1957, when the last execution was carried out. This makes for a far better record than any of its neighbours. Thankfully the international outcry encouraged them to extend the moratorium to include the new Sharia code, so none of the barbaric penalties it prescribes have actually been carried out.

On my first day in BSB, I visited Kampung Ayer. Kampung Ayer is a huge neighbourhood on stilts, built above the Brunei river that traverses the city. For centuries, this neighbourhood was the capital of the Bruneian empire. It was only in the 60s and 70s that most of the population was encouraged to resettle on solid ground. The neighbourhood is still alive and kicking, with about 10,000 people living there. It may well be the biggest settlement on water in the world today.

To get to the settlement, I had to take a speedboat across the river. As soon as I showed up on the shore, a driver stopped and offered to take me across. The crossing cost the very reasonable sum of 1 Brunei dollar (about 0.7 Euro). I was left at the “official” entrance to Kampung Ayer, next to a museum on the neighbourhood’s history.

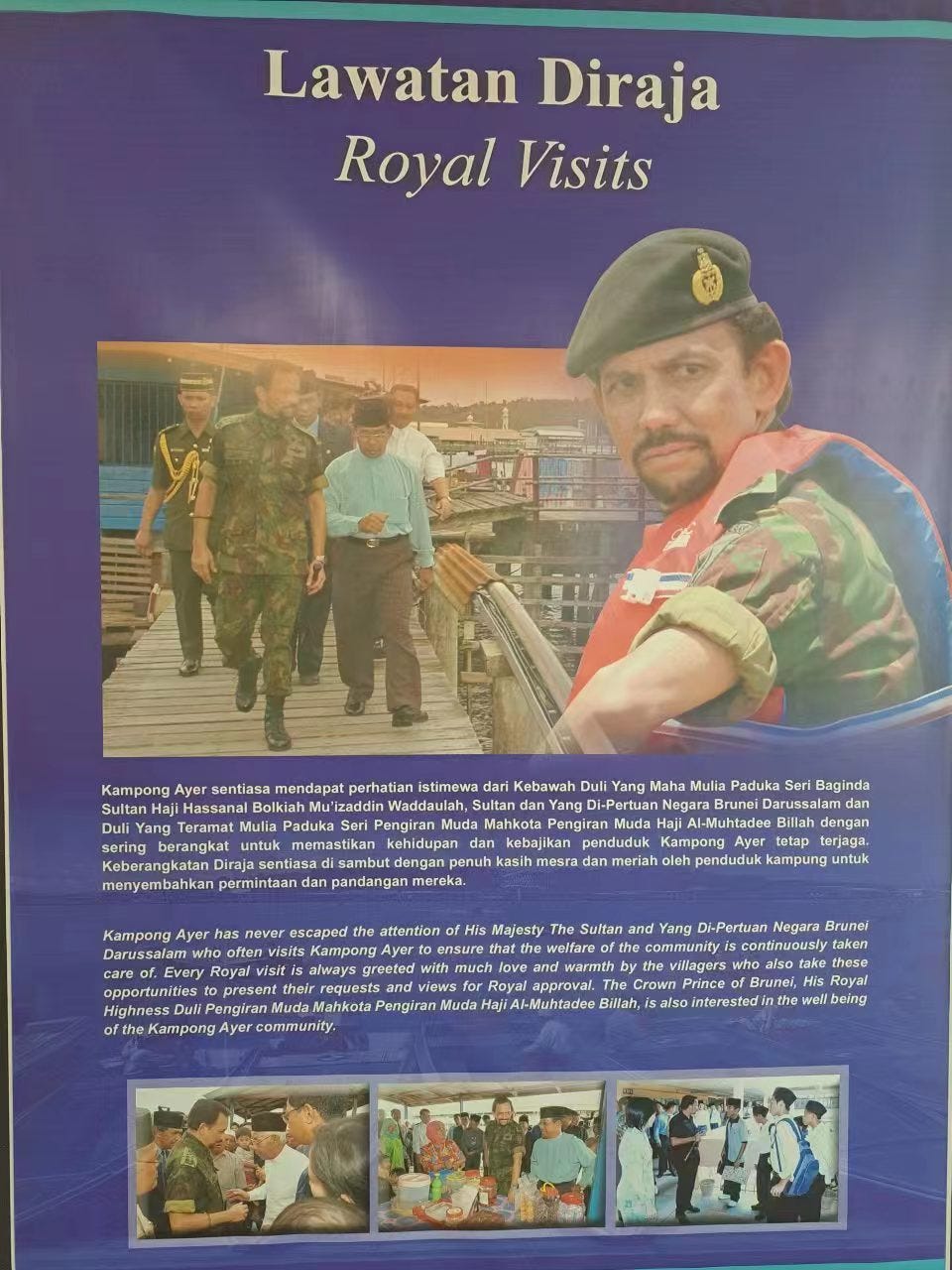

The museum proudly mentions that Venetian traveller Antonio Pigafetta, who joined Magellan on the world’s first circumnavigation, called the city “the Venice of the East” in 1521. It’s a rather ambitious assessment if you look at the place today, but at the time the Bruneian Empire was at its peak, and the capital was probably quite impressive. The museum also included displays on the area’s traditional crafts, and of course some fawning panels on the Sultan’s latest visits to the neighbourhood.

After leaving the museum I walked to the nearby observation deck, alongside a pathway clearly built for tourists, and then I ventured into the neighbourhood itself, something which few visitors seem to do. I can see why. The boardwalks suddenly became simple series of wooden planks, with no railings, suspended a few metres above water. What’s more it was obviously low tide, and in many areas there was no water down below, just mud and the occasional wooden or metal pole sticking out of the ground. Falling off the edge would have been dangerous.

The neighbourhood is really very big. It didn’t exactly feel packed, but there were certainly people going about their lives, walking along the wooden planks above the river. While there were some new government-built houses in the area adjacent to the museum, once I got further inside the wooden houses started to look old and even decrepit. Ironically this neighbourhood on water is at constant risk of fires. The latest fire in 2020 left 100 people homeless.

In spite of Brunei’s wealth, Kampung Ayer didn’t feel at all wealthy. Most of those who still live in it tend to be elderly, or else they are foreign immigrants from Malaysia and Indonesia, attracted by the low rents. They commute by boat to the Mainland on a daily basis. Few people still make a living from traditional crafts and jobs, like building ships and fishing. There are fewer fish in the river than there used to be, as the water quality has worsened. The fact that the older houses have no real sewage treatment doesn’t help to keep the water clean.

I kept moving further and further into the neighbourhood, watching my step as I negotiated the rickety walkways. It was extremely hot and I wanted something to drink, but I could spot no shops or restaurants. I finally asked a middle-aged woman where I could buy water. I asked in English but she didn’t understand, then I asked in Indonesian and she not only understood but walked me to the closest restaurant (Indonesian and Malay are essentially one language).

The restaurant looked cheap and rustic. I bought a soft drink, then I walked on until I reached the bank of the river, and immediately a speedboat stopped to pick me up. It was the same driver as before. I paid another dollar, and he took me back to the city.

Brunei’s capital has few sites apart from Kampung Ayer, but it does have the Royal Regalia Museum, which displays the gifts that the Sultan has received from around the world. A much better use for them than keeping them locked up in his palace, I suppose.

The museum is huge, full of gifts from the world’s monarchs and presidents, as well as displays of the chariots used during the sultan’s coronation and silver jubilee celebrations. There are literally floors and floors of displays. It is all very well curated and presented, in both English and Malay. You have to leave your shoes at the entrance of the museum, as if it were a mosque, and you officially aren’t allowed to take any photos.

The Sultan of Brunei is certainly the country’s most well-known figure. Hassanal Bolkiah ibni Omar Ali Saifuddien III, now 77, has been on the throne since 1967. Now that Queen Elizabeth is gone, he is the longest-reigning monarch in the world. He is also one of the world’s richest men, and one of very few absolute monarchs left anywhere. As well as being the sultan, he is also the prime minister, finance minister and defence minister.

It is interesting to read about how this unusual little country became the way it is. Essentially it all revolves around oil and Britain. Brunei was a full British colony until 1959, when a new constitution granted it self-government. Foreign affairs and defence remained in the hands of the British until 1984, when Brunei became fully independent.

In the country’s first and only elections, in 1962, all seats were won by the Brunei People’s Party, a left-wing party which favoured Brunei joining the new Federation of Malaysia, but on condition that Brunei, Sabah and Sarawak could first unify under the sultan of Brunei, who had traditionally ruled the whole region.

There was support for this idea throughout North Borneo, as it was thought that such a sultanate would be strong enough to resist domination from the more populous Peninsular Malaysia. The local population felt a strong sense of difference from the Malays of the peninsula. There was also a military wing of the Brunei People’s Party, however, which favoured joining Sukarno’s Indonesia, which at the time was claiming the whole of Borneo and boasted better “anti-imperialist” credentials than Malaysia.

The Party demanded the Sultan devolve more power to them, but he refused to cooperate, so in 1962 they staged an armed revolt. The revolt was put down in two weeks with the strong help of the British army, and the BPP was banned. The Sultan had been considering whether to join Malaysia himself, but in the end he decided against it. He did not want to see Brunei’s oil revenues dispersed throughout Malaysia, and the outcome of the revolt convinced him that the British had his back.

Since 1962, there have been no challenges to the sultanate’s power, and Brunei has been completely depoliticised. There is no other country in Southeast Asia with no organised opposition or civil society of any kind. The redistribution of oil money has bought public support. Just like the Gulf countries, Brunei can be generous with its citizens: there is no income tax, and education and healthcare are free and good quality. They call it a “Shellfare state”, since Shell runs the oil rigs.

In case you are tempted to be cynical about Britain’s role in all this, it must be added that after the revolt the British government continued to pressure Brunei to democratise and join Malaysia. The Labour government that came to power in 1964 was particularly eager to withdraw its troops from Brunei, rather than letting it become the Sultan’s permanent defence force.

The Sultan resisted the withdrawal, however, and apparently threatened to transfer his entire fortune from the British bank where it was deposited. His money was valuable to cash-strapped postwar Britain, and Shell supported the sultan because they wanted continued access to Brunei’s oil, so in the end London relented. Even after full independence in 1984, the current Sultan has continued paying for the British army to remain stationed in the country, as a guarantor of its (or his) security.

Foreign tourists aren’t particularly frequent in Brunei, and people were often quite eager to chat. During my four days there, I got to know local people on a couple of occasions. The Chinese man who gave me a lift from the station bumped into me again in the city centre a couple of days later. He took me into his glasses shop, where I had a long chat with him and his family, while they offered me coffee and sweets.

The man and his wife and teenage son were clearly well-educated and multilingual. The son told me he was getting ready to go to university in Malaysia. They spoke to me in fluent English, but the old grandmother sitting in the corner was reading a newspaper in Chinese, and they spoke to her in Hokkien. They also understood when I spoke in Mandarin. I assume they must have spoken at least English, Mandarin, Hokkien and Malay with some degree of fluency. Such multilingualism isn’t unusual in Brunei and Malaysia.

They were all very nice, and asked me all kinds of questions. The man’s wife was surprised when I said my next stop would be Pontianak (“but there’s nothing there! Oh well, I guess you like seeing the world”). I was rather struck, though, when the conversation turned to geopolitics and she started voicing opinions which clearly mirrored the narratives you hear from government media in China.

I had a distinct feeling that she must have been getting her news from China-aligned media. I had heard that the Chinese in Malaysia (and I would suppose Brunei is the same) increasingly consume media from China, or local Chinese-language media that is now controlled by groups close to the Chinese Communist Party. This experience seemed to confirm it.

On my last day in Brunei, I also got to know a local couple at the pool in my hotel. They were around 30, and the woman was swimming fully clothed, in typical Muslim style. They were very friendly and spoke decent, if not quite fluent, English. They told me about how young Bruneians sometimes take trips to the nondescript town of Miri, just across the Malaysian border, to enjoy the nightlife and drink alcohol.

They were not dissatisfied with their country, however. At one point I asked them if they thought it was a good thing that Brunei didn’t end up joining Malaysia, and they said they did. Brunei was prosperous and safe. They particularly stressed the country’s safety, as compared to supposedly much more dangerous Malaysia. I don’t find it hard to believe that Brunei has particularly low crime rates, since it is small and highly controlled.

In the end, the couple offered to drive me in their car to the Gadong night market, where Bruneians like to go for dinner. It was very nice of them, and I would not have thought of going there on my own. The market was packed with people, and it was full of cheap and extremely good food.

After the night market, they took me to see the massive Jame' Asr Hassanil Bolkiah Mosque. It is one of Brunei’s two state mosques, alongside the already mentioned Omar Ali Saifuddien Mosque. This one was also designed by a European, the Englishman John Lawson, and opened in 1994.

It’s even bigger than the other one, and able to accommodate 5000 worshipers at once; it has 29 golden domes and four 58-metre minarets. It was certainly quite a sight to behold. There is also a special escalator into the mosque reserved for the Sultan, reminding me of the special gate in Beijing’s Forbidden City which only the emperor would use to enter.

Later the couple dropped me off at my hotel, and after profusely thanking them for the company and the impromptu tour, and adding them on Instagram, I went to bed. The following morning I packed my stuff and went to get the coach to Indonesia. I had enjoyed my four days in Brunei.

"Malaysia remains peaceful, having seen its last explosion of inter-ethnic violence all the way back in 1969."

The Chinese-minority-centred communist insurgency in Malaysia continued fitfully until 1989. I've read accusations that PLA officers deployed to back up Chin Peng's men but never anything solid on this. The connection between Malaysian ethnic-Chinese and China has always been present, including influence over local media, which has no doubt grown stronger in recent decades as you note.

Good write up. Makes me miss my travelling days.