Although I am an adventurous traveller, I have never been a reckless one. I like travelling to places that are off the beaten path, but I don’t like putting myself (or others) in danger. I don’t go to conflict zones, and I generally avoid places which my government warns its citizens not to visit.

Last week, however, I broke the last rule: I visited the “deep south” of Thailand. Thailand’s southernmost provinces of Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat have long been considered unsafe for tourists. The British government currently warns against “all but essential travel” to the three provinces, as well as the southern part of adjacent Songkhla province. Other Western governments have similar warnings in place.

Thailand’s deep south is inhabited mostly by Malay-speaking Muslims, and in many ways it has more in common with Malaysia than Thailand. The area has never really adjusted to Thai rule, and it is the scene of a long-running insurgency against the Thai state. The insurgency became much more violent around 2001, and since then there have been constant terrorist attacks in the region, which is why travel there is not generally advised.

I began my journey in Hat Yai, the main city of Songkhla province. This province is sometimes also considered to be part of the deep south, but it is more culturally aligned with the rest of Thailand. Only around a third of the province’s inhabitants are Muslim, and most of them speak Thai rather than Malay. It is generally seen as safer, although it has also been affected by the unrest in the past.

Hat Yai is the largest city and transport hub of the whole Southern Thailand. It has become a major destination for Malaysian tourists, since it is in easy reach of their country and offers affordable halal food, shopping opportunities and a freewheeling Thai atmosphere.

I stayed in a hotel right in the middle of Hat Yai. The city centre felt quite touristy, with signs written in Chinese and Malay as well as Thai, and street markets catering to the plenty of Malaysian and Singaporean visitors who throng the streets. It is not a destination that is popular with Westerners; I barely saw any farang at all while I was there.

There is a well-known “floating market” called Khlong Hae just outside the city, so I took a taxi and went to have a look. Thailand’s floating markets are famous, but I had never been to one before. Unfortunately it was raining when I got there, which somewhat dampened the mood. Nonetheless the market was in full swing, and there was a section where people really were selling food from boats on a river.

Most of the vendors were Muslim, with the women wearing hijabs and the men wearing songkok (the little round hats worn by Muslim men in Southeast Asia). The food was all unfamiliar and, not knowing what to choose, I ended up eating some rather indifferent rice with chicken. Later I went back to the city and bought some more food at a street market just outside my hotel. While I sat eating, a group of young tourists asked if they could sit next to me. I heard them speak to each other in Mandarin, so I replied in Mandarin and we started chatting.

They said they came from Penang, the famous Malaysian island which is just a three-hour drive from Hat Yai. Like many young Chinese-Malaysians they had gone to Mandarin-medium schools and spoke the language completely fluently. They were very friendly and offered me some of their food, which included a noodle dish with little shrimps that were still alive and jumping up and down on top of the noodles. You wait until they stop jumping, and then you start eating. This is one dish I had not yet encountered in all my travels around Asia.

Songkhla

The following morning I took a bus for the one-hour ride to the coastal town of Songkhla, the provincial capital. Songkhla is smaller than Hat Yai, but it has a long and distinguished history. By the 10th century it was a major centre of international maritime trade, particularly with China. In the 17th century it became the seat of the Sultanate of Singora, which was founded by a Persian Muslim.

The sultanate came under the sway of the Siamese (Thai) kingdom of Ayuthaya, and when it tried to break free it was destroyed by a Siamese army in 1680 after a six month siege. The Siamese then attempted to cede Singora to the French, who made it clear however that they were not interested. In the end the town fell firmly under Siamese suzerainty, alongside the rest of the region.

Songkhla has a significant Chinese presence, since plenty of immigrants from Guangdong and Fujian made it their home starting in the 18th century, and after the fall of the sultanate local politics was dominated by Chinese families. After World War II, changing trade routes and the rise of nearby Hat Yai with its airport led to a decline in Songkhla’s importance, and the town now has an aura of faded glory.

Songkhla is still very conscious of its heritage however, and recent community-led efforts to renovate its old town have led it to become a trendy destination for Thai tourists. The old town sits on the shore of the large Songkhla lake. The streets are lined with old houses built in the Sino-Portuguese style, a unique blend of Chinese and Portuguese architecture, interspersed with Chinese temples. It’s all quite gentrified, with houses converted into fancy cafes, restaurants and artsy shops. Some of the walls have murals depicting street scenes from the past.

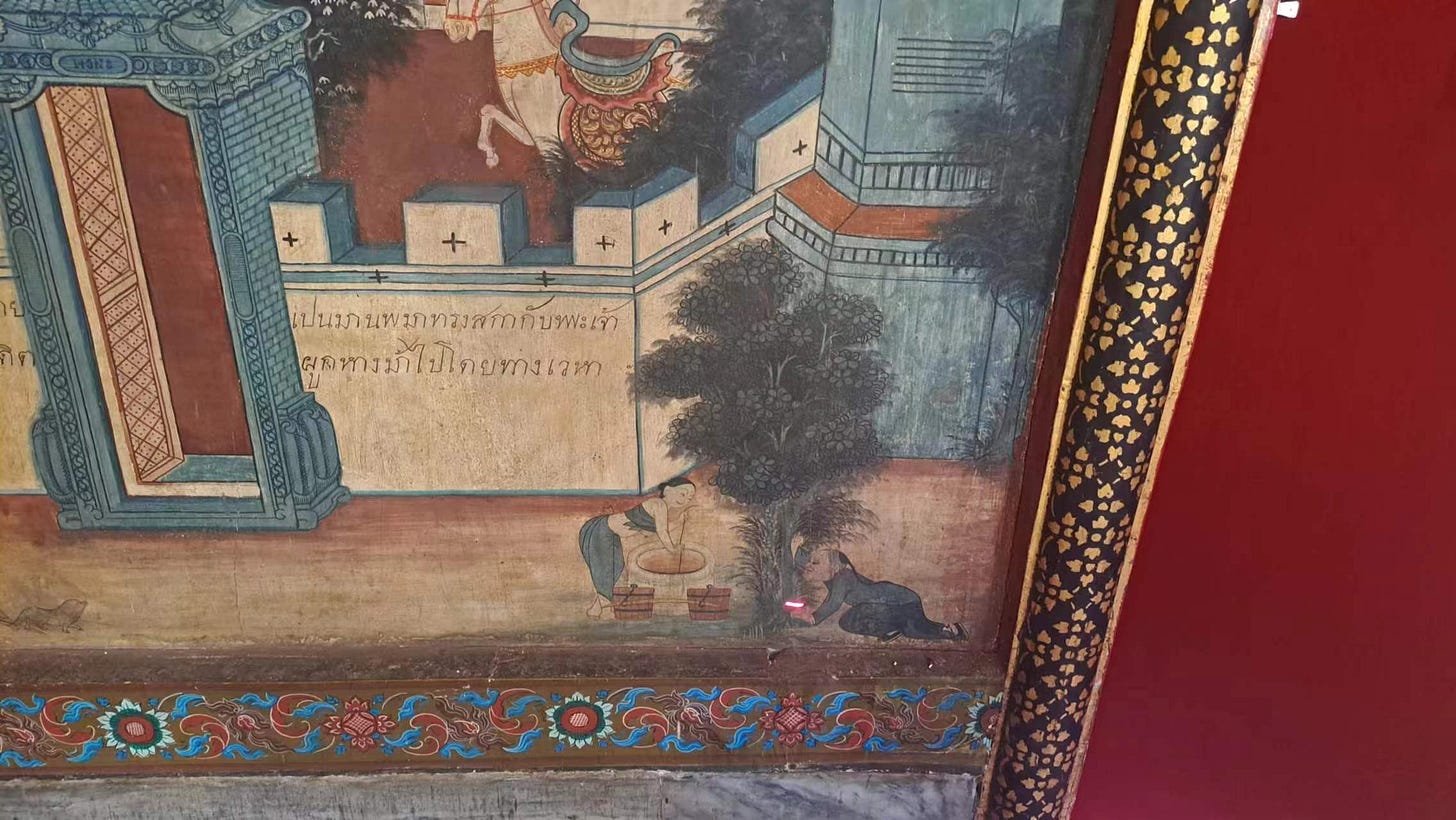

I stopped at a house that has been converted into an interesting exhibition of ceramics (photos below), and then I wandered around until I came across Wat Machimawat, Songkhla’s most renowned temple. Established in the 17th century on land donated by a rich Chinese merchant, it is built in a mix of Thai and Chinese styles. The ordination hall, built in the 19th century, includes some very interesting paintings on the walls.

As I stepped inside, a lady who works for the temple approached me. She was very keen to guide me around, explaining the meaning of the murals. I did not have to pay a ticket to enter, and she never asked for any payment either. She seemed to be genuinely enthusiastic about sharing her knowledge with me. In understandable English, she explained how the paintings depict scenes from the life of Buddha, interspersed with illustrations of daily life in the Songkhla region during the 19th century.

She pointed out various details in the paintings that I would have missed, including an image of a Chinese man with the typical Manchu pigtail of the Qing Era, who seems to be spying on a local lady fetching water from a well; and an image of a shipwreck, with the nose of a sawfish emerging out of the water. Sawfish live in Songkhla lake, and apparently their long noses lined with teeth are considered holy and can be found in local shrines.

Two Chinese ladies, a mother and a daughter, entered the hall and started listening to the guide as well. I chatted with them a bit in Chinese, and they said they came from Shenzhen. The daughter was attending a scientific conference in town, and she had brought her mother along for a holiday.

At one point, the younger Chinese woman had a very odd question for the guide: she wanted to know if there was a risk that marijuana would be put in their food in the local restaurants in Songkhla. The guide didn’t understand the question at first, but I did and I told her there wasn’t a chance in hell. I explained that while marijuana and hashish have indeed been legalised in Thailand, you have to go to special stores if you want to buy the stuff.

Since Thailand legalised light drugs in 2018, the Chinese authorities have started doing random drug tests on people who fly in from Thailand (god forbid their citizens develop a taste for such things while holidaying abroad). The two ladies from Shenzhen were aware they might be tested after going back, and they were apparently afraid that marijuana could be slipped into their food without their knowledge.

Chinese tourists’ visits to Thailand have already declined significantly this year, due to completely unfounded fears that Thailand is dangerous, fanned by the Chinese media. Perhaps stories of Thai restaurants using pot as an ingredient are now making the rounds as well.

After saying goodbye to the friendly guide and the two Chinese ladies, I went back to my hotel. Later in the afternoon I walked to Samila Beach, the town’s most popular stretch of sand. The beach includes a statue of a mermaid created in 1966 by Thai artist Jitr Buabus, based on a character from the 19th century Thai epic poem Phra Aphai Mani. Thai tourists love having their photo taken next to it. A bit further from the sea there is another statue of a cat and mouse, related to a local legend about the origin of two nearby islands, known as Cat Island (Ko Meow) and Mouse Island (Ko Nu).

The following morning I rented a scooter and drove to Ko Yo, an island that sits in the middle of Songkhla Lake. The island is connected to the Mainland by two long, modern bridges which are a pleasure to drive across. On top of a hill on the northern tip of the island there is a “Folklore Museum”, which I visited.

Songkhla’s National Museum, highly recommended by guidebooks, is closed on both Mondays and Tuesdays, so given that I arrived on a Monday I was unable to visit it. I wasn’t expecting too much from the Folklore Museum, but it turned out to be extremely big, and to have lots and lots of interesting relics and exhibits showcasing Songkhla’s long history as a port trading with the rest of Asia. The links with China were particularly clear from all the Song, Ming and Qing vases and artwork on display.

After leaving the museum I drove to Singkhanakon, a district north of the city where you can find a few remains of the old Sultanate of Singora. The area contains the remnants of a number of fortresses and walls from that time, scattered around the rural suburbs. I walked up a long flight of steps on the side of Khao Daeng Mountain to see the remains of Fortress No. 8, the most accessible one in the area. The remains of the fortress are not all that impressive, to be honest, but they do afford a nice view of the surrounding area.

Pattani

The following day I left Songkhla and travelled by bus to Pattani, the most important town in the three Malay Muslim provinces of Thailand’s “deep south”.

Although travel to the area is generally discouraged, a bit of research convinced me that there is nothing to worry about. Those who have visited in recent times unanimously say it is safe. The insurgents have never intentionally targeted tourists or foreigners, and the only risk is being in the wrong place at the exact moment a bomb goes off, which is exceedingly unlikely. Driving a scooter in Phuket or Koh Samui, like many tourists do, is certainly more dangerous.

Admitedly, the insurgency in Southern Thailand is no joke. The conflict reached its peak in the years between 2004 and 2016, when the violence was causing hundreds of victims every year, in a region with just over two million people. Currently the death toll still stands at dozens of people a year, with 49 official victims recorded in 2024.

The roots of the conflict lie in the mismatch between old and new concepts of sovereignty. From 1400 to 1902, the area was run by the Sultanate of Pattani. In spite of being Muslim and Malay, for various reasons the sultans paid tribute to the Siamese (Thai) rulers in distant Ayuthaya and later Bangkok. This does not mean that the region was “part of Siam” in any modern sense, however. In practice they were left to look after their own affairs, and only had to send a symbolic gift of golden and silver trees to the Siamese court every three years.

Things changed in the 20th century. In 1902 Siam deposed and arrested the last sultan of Pattani, imposing direct rule, and then in 1909 the Anglo-Siamese treaty delineated the border between Siam and British Malaya, recognising the area as part of Siam. In the 1930s the centralising dictatorship of Marshal Phibunsongkhram, which formally renamed Siam as Thailand, established policies of enforced assimilation, mandating that all schools teach in Thai alone and replacing traditional Muslim courts with state courts that answered to Bangkok.

Things have relaxed a bit since then, and primary schools in the region now teach bilingually. However demands for greater cultural and legal autonomy have generally been rejected, and this led to decades of creeping separatist violence starting in the mid 20th-century, which escalated considerably after 2001.

The insurgency is carried out by a confusing array of underground armed groups, all of which now profess some sort of allegiance to Salafi ideals. The most important separatist group used to be the Patani United Liberation Organization, founded in 1969, which had a secular nationalist ideology and was focused mainly on liberating the South from Thai “colonialism”. Over the last decades, however, the fight has been taken over by groups with extreme religious views, mirroring what has happened to similar struggles in the rest of the Muslim world. These groups seem to have no realistic goal except making the area ungovernable.

The insurgents have committed extremely nasty actions, murdering anyone they see as representatives of the Thai state, including teachers and civil servants we well as policemen and soldiers. They have killed Buddhist monks and Buddhist villagers, and left bombs in public places which have hit anyone who happened to be passing by. As is often the case in these situations, the Thai security forces have also been guilty of human rights abuses, torturing and killing suspects. The worst case of abuse by government forces, the Tak Bai incident of 2004, shocked the public throughout Thailand.

While things have improved since then, the situation is still tense. Just a few days before I visited, Pattani was rocked by the explosion of two bombs hidden in bins, one of which lightly injured a vendor in a night market. When I mentioned to a restaurant owner in Songkhla that I was going to visit Pattani, she urged me to reconsider. She said at most I should go for a day, but not stay overnight. Thais in the rest of the country will often try and dissuade you from visiting the deep south.

Still, I had already decided to go, and my research led me to believe that I would be in no particular danger. Before going I booked a room in the fanciest local hotel, CS Pattani, where visiting government officials often stay. I figured this would be a safe choice. A room booked online cost me about 42 USD.

When I arrived in Pattani I found that the town only seems to have motorbike taxis, so I took one to my hotel. I sat on the back with my suitcase balanced on my knee, without wearing a helmet. Grab drivers will almost always have an extra helmet to give you in Bangkok, but in small towns this cannot be expected.

The hotel was very comfortable and had an old world charm. The lobby was full of local artwork and artefacts. The artefacts, the people and the general atmosphere reminded me more of Indonesia than of Thailand. There was a metal detector at the entrance to the lobby, a reminder of the risk of terrorist attacks, although it wasn’t actually in use when I was there.

That evening I went out for a walk in the centre of Pattani. The unrest has stunted the economic development of this town that used to be the capital of a prosperous sultanate, and it looked noticeably poorer than towns in Central Thailand. There were policemen stationed at every intersection, but otherwise everything felt normal. The police were not at all concerned by my presence, and the locals were friendly.

The deep south of Thailand is very conservative, perhaps as much as neighbouring Kelantan, the most strictly Islamic state in Malaysia. Most women wear a hijab, and quite a few even wear the full face veil which only leaves the eyes visible. There is however a minority of non-Muslims also living in Pattani.

The next day I moved to a cheaper hotel in the town centre, and then I walked to Pattani’s Chinese quarter. Just like most towns in the region, Pattani has had a significant number of Chinese residents since at least the 16th century. My goal was to visit the Chao Mae Lim Ko Niao Shrine.

This shrine is dedicated to the local Chinese deity Lim Ko Niao (林姑娘, or Maiden Lim). Next to the shrine there is a small museum about this mythical figure. Unfortunately the explanations are only in Thai, but with the help of Google and the odd Chinese inscription I managed to piece the story together.

According to local legend, Lim Ko Niao was the sister of Chinese pirate Lim Toh Kiam, an actual historical figure who settled in Pattani in the 16th century. Local lore has it that Lim Toh Kiam married the daughter of the local sultan and converted to Islam. Lim Ko Niao is supposed to have gone looking for her brother when their mother fell ill back in China. She found him in Pattani and tried to convince him to return home to China, but he refused. Instead he fought her and won. After this she hanged herself from a cashew tree.

Lim Ko Niao is now worshipped by the local Chinese community as a symbol of filial piety and Chinese patriotism. A festival is held annually to celebrate her, with a grand procession that carries a statue of the goddess through the streets of the town. Reportedly many local Muslims are quite happy to take part in the festivities.

That afternoon I hired a driver to take me to a few sites outside the town. The first one was the Krue Se mosque, Pattani’s most historic mosque, first built in the 16th century. It is the holiest mosque in the region and a symbol of local identity, but in 2004 it was the scene of an infamous battle when 32 insurgents sheltered inside the mosque after being involved in a series of attacks against the police. After a siege lasting several hours, the army stormed the mosque (contravening orders from the government) and killed all 32 of the militants on the spot.

When I visited there was an unmanned military checkpoint on the street outside the mosque, with barbed wire and bags of sands. The mosque is a small building made of red bricks which looks distinctly old, with Middle Eastern-looking archways and loudspeakers on top to broadcast the call to prayer. People were praying inside the mosque so I couldn’t go in, but I looked around outside.

The tomb of Lim Ko Niao, the aforementioned Chinese folk heroine, stands right next to the mosque. Local legend has it that her brother, the Chinese pirate who converted to Islam, was actually the one who built the Krue Se mosque. Lim Ko Niao is said to have cursed the mosque before she died, so that lightning would strike whenever someone tried to complete it.

According to legend, three times a dome was built above the mosque, but every time lightning reduce it to rubble. The top of the mosque still looks unfinished. Lim Ko Niao’s gravestone, which was probably created in the early 20th century, was placed right next to the mosque which she supposedly cursed, and no one seems to have a problem with this.

After the mosque, my driver suggested we stop at the Old Palace of Yaring. This is the former residence of a local governor, built in 1885. It was designed by an Indonesian, so it has Javanese as well as European and Thai elements. The residence is made of teak wood and is well preserved. The descendants of the governor still live there, but you can visit by paying an entry fee of 30 baht.

I told the guide, a lady in a hijab, that I don’t speak much Thai but I can speak some Indonesian. She then spoke to me in Malay, which I could more or less follow. When the guide and my driver spoke to each other in what I assume to be the local Malay dialect, I understood nothing; but her formal Malay was close enough to Indonesian that we could understand each other.

After seeing the palace, I asked the driver to take me to nearby Talo Kapo Beach. I arrived and found quite a few local families on the beach, even though it was a weekday. The travel advisories are very effective at keeping foreign tourists away from Pattani, but locals also go to the beach. Next to the sand there was a run-down market and some rustic cafes.

The region’s conservatism was very apparent. Most of the women on the beach were draped in black veils, and even the men were wading into the water fully clothed. People stared at me in surprise, while brave children tried to address me in English. I walked on until I found an area with no people, and I relaxed on the sand under the palm trees.

As we drove back into town I noticed a few army roadblocks, and we went past a police station that was surrounded by elaborate military-grade defences. The region’s problems are obvious mostly from the heavy presence of state security forces.

That evening, back in town, I tried to walk to a Chinese vegetarian restaurant recommended by Lonely Planet, but the restaurant has either closed down or it is not where Google Maps claims it to be. In the end I ate at a steakhouse near my hotel, perhaps the only restaurant serving Western food in Pattani, apart from the inevitable KFC.

The following morning I took a bus to Hat Yai, and from there I flew back to Bangkok.