And so it was that, on a rainy Wednesday morning, I headed from the small volcanic island of Tidore to its much larger neighbour, Halmahera.

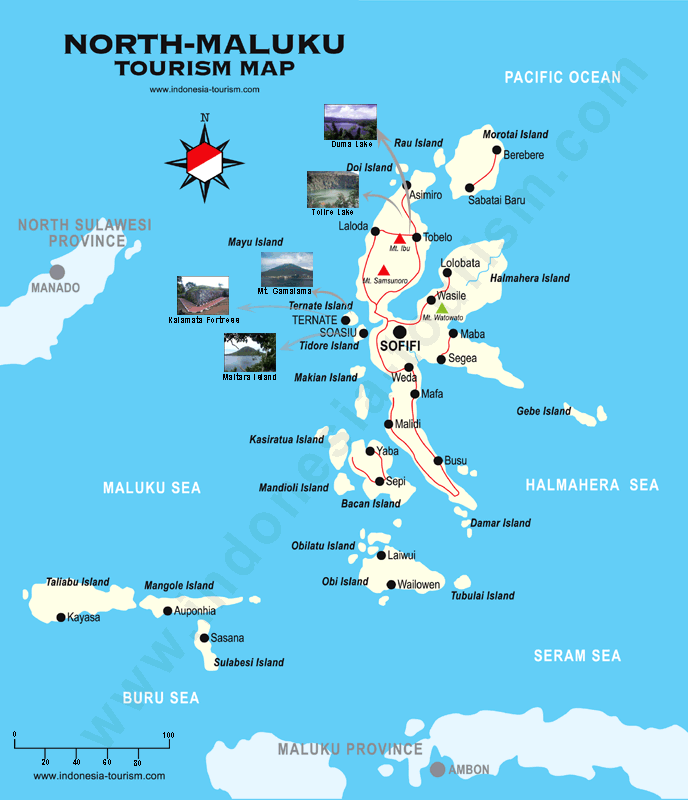

Halmahera is the biggest island in the Moluccas, around 50 times larger than tiny Ternate and Tidore combined. It’s a size comparable to Sardinia, but it’s spread out into an odd K-shape with four distinct peninsulas, making it far longer than Sardinia from one end to the other.

Halmahera is scarcely populated, with only 450,000 people, and mostly covered in rainforest. Although it also hosted an Islamic sultanate in the past, in the town of Jailolo, most of the island was historically governed by the sultans of Ternate and Tidore, who saw it as a vast hinterland where food could be grown.

I got to Halmahera by taking a speedboat from Tidore to the town of Sofifi, on the west coast. The speedboat, which held maybe a dozen passengers, took half an hour and cost about 3 Euros. Sofifi was made the provincial capital of North Maluku in 2010, but this has done little to encourage development. The town remains small, scruffy, and extremely underwhelming. Government officials must dread getting posted there.

From Sofifi’s harbour I took a shared taxi to Tobelo, Halmahera’s largest town, in the Northeast of the island. I had to wait about an hour at the harbour while the driver looked for one more passenger so his car would fill up. The journey took four hours and cost me about 12 Euros.

The taxi cut across the island, winding through pristine rainforests and languid coastlines, and occasionally driving through small villages. My phone didn’t have any signal during most of the ride. The road was in good condition, however. Roads in Indonesia seem to be quite decent, even in the remotest areas. This is quite a contrast with Cambodia, which I visited two months ago, where even national highways can be appalling and full of potholes.

Most of the villages we went through had churches; Halmahera has both Muslim and Christian areas, with Christians seemingly the majority in the North. Both the churches and the mosques I saw looked big and pompous next to the simple wooden houses where the people lived.

Things are peaceful today, but when religious and ethnic conflict flared up in the Moluccas in 1999, during the chaos that followed the end of Suharto’s regime, Halmahera was hit very badly. The unrest in North Maluku started off precisely in the areas I was driving through, when fighting broke out between the locals and immigrants from Makian, another Moluccan island whose volcano erupted in 1988, forcing the inhabitants to temporarily evacuate in mass to other islands.

The Makianese were Muslims, and many of the locals Christian, but initially the unrest appears not to have been motivated by religion. It was more an issue of competition over resources and anger at a government plan to carve out a new sub-district for the Makianese. Things escalated and the fighting took over the whole region, turning into a nasty religious conflict between Christians and Muslims, as well as a struggle for the governorship of the newly created province of North Maluku which pitted the sultans of Ternate and Tidore against each other. The violence left a few thousand dead and created refugees across the region.

The taxi dropped me off at Kupa Kupa, a village south of Tobelo. The village has a beach, and I had found out that there is a beach resort with bungalows run by a German man and his local wife. I marvelled that somewhere so remote would even have such a place.

It turned out that I was the only guest at the resort, which didn’t surprise me one bit. The German owner, only the second other white person I’d seen in North Maluku, looked very elderly and seemed to spend most of his time sleeping in the shade. His wife and her niece ran the resort. When I arrived, he arose from his slumber to ask where I came from, but we never spoke again. About a week after returning to Bali I got a WhatsApp message from the niece, saying that the German man had died. I was sorry to hear it.

The resort’s bungalows were divided into cheaper ones, which cost 350,000 rupiah a night (around 20 Euros), and more expensive ones, which cost 500,000 (around 30 Euros). The more expensive ones were comfortable and had air conditioning, although still no hot water (I no longer expected this in Maluku). The cheaper ones were very basic, with a traditional Indonesian bathroom with no sink or flush toilet.

The price included two good meals a day, so you never had to leave the resort. The beach was another piece of tropical paradise, which I got to enjoy in almost Robinson Crusoe-like isolation at times. The only thing that spoiled the scenery somewhat was a big coconut oil processing factory sitting just next to the beach.

I had a chat with the lady who ran the resort, the wife of the German man. She was from the area but had gone to Ternate as a teenager to work as a maid for a family of Chinese descent. She had returned at 30 and started the resort. She told me that while the factory I could see from the beach was Indonesian, there was another Chinese-owned one in the area.

She said that the Chinese company wanted to buy her land, so they could build a dormitory for workers on the beach, but she had always refused and would continue to do so. She started complaining about the Chinese, saying that she no longer liked going to the East of the island because they were destroying the rainforest there. “Even the Europeans never did this in the past”, she added.

Life in the resort was idyllic, but the only problem was that there was no wifi, and even the 4G connection was weak in the area, so that using a personal hotspot also wouldn’t work. The nearby village of Kupa Kupa just had some simple shops and restaurants and wasn’t the kind of places where you could find a wifi connection.

I had some work to finish on the day after I arrived, so I had to go to Tobelo to find a place with wifi. From the village I caught a shared taxi into town. Tobelo is the most developed town on Halmahera, but that’s not saying very much. There is a main shopping street next to the harbour, but it is quite run down and rather dull.

The town has one fancy bakery/café with air conditioning (“European conditions but Indonesian prices”, I had been assured), but it turned out not to have wifi. Luckily I found another café/restaurant, mentioned in Lonely Planet, which did indeed have wifi. It was outdoors and the heat made working there rather uncomfortable, but I had no other option. Tobelo is certainly no place for digital nomads.

After finishing my work, I caught a bemo back to Kupa Kupa. It was horribly hot inside the vehicle, and we had to wait until it was full to set off. Then the driver kept making long stops to pick up unidentified bags of stuff. There was also local reggae-style music playing at full volume inside the bemo. I resolved to rent a scooter if I had to go into town again.

The village of Kupa Kupa was obviously Christian, as the churches and the cemetery made clear. The simpler local houses were made of wood and built on stilts, while others were made of concrete. The local language of the area, known as the Tobelo language, is one of six Papuan languages spoken in Northern Halmahera. In the South, people speak completely unrelated Austronesian languages. That’s a lot of linguistic variety for an island with so few people.

I spent a few days kicking back at the resort, and I even tried my hand at snorkelling, which was quite rewarding. There turned out to be plenty of brightly coloured fish, coral and starfish just a few meters from the shore. The food at the resort was good, and they even had beer and wine available, this being a Christian area.

After a couple of days I moved into one of the cheaper bungalows to save money, but the rather basic conditions and the presence of large cockroaches soon begun to get me down. Fortunately after two nights the lights in my room broke, probably because hundreds of tiny ants were crawling inside the switch and damaging the wiring, so I got upgraded to one of the nicer bungalows again.

The resort offered trips into the rainforest, so I decided to go on one. The niece of the owner, a girl who might have been in her late twenties, acted as my guide. We drove on her scooter for ten minutes to the edge of the village, where the jungle began. Then we parked the scooter and walked into the wilderness. In the beginning there was a path, but it soon disappeared, replaced by a faint mud track left by the few people who walk into the forest.

My guide took out a large kitchen knife, which she used as a machete to clear the way. We trekked onwards for an hour or so. We saw some huge black birds up in a tree, and a massive spider in the middle of a web with gold and black stripes on its back, which both fascinated and repulsed me. I was assured there are no dangerous large mammals on the island.

As we trekked, I chatted with my guide. She had gone to high school in Jayapura, in Papua, and surprisingly spoke English with a distinct British intonation, which she had picked up from a British teacher.

She told me that just a few weeks earlier she had gone to the jungle of Eastern Halmahera and visited a settlement of the indigenous, semi-nomadic tribes who still live there. Known as the Tonggutil, they are one of Indonesia’s last tribes of hunter-gatherers, a few thousand people who live deep in the jungle and continue to stick to their traditional lifestyle, wearing traditional clothing and living off the land. They follow animist beliefs, and a few hundred of them remain essentially uncontacted.

My guide said she is involved with an NGO that helped to secure land rights for these communities and ensure that they can maintain their lifestyle (which includes, apparently, not having to send their children to modern schools). She showed me a photo of herself in the jungle with an old lady from the tribe who wore traditional clothing and had exposed breasts. The Tongutil speak a variant of the Tobelo language, and my guide said she was able to understand them once she got used to their way of speaking.

Unfortunately, these tribes’ way of life is now seriously threatened by the mining of nickel that is going on in the region, to power the world’s thirst for electric car batteries. The mining is hacking down parts of the rainforest. Considering the complaint I had heard previously about the Chinese companies destroying the jungle, it would seem the resulting environmental damage doesn’t only bother the small hunter-gatherer tribes, but quite a lot of the island’s inhabitants.

In any case, the rainforest I was trekking in was thankfully still intact. We reached an opening in the trees, with a river running through it. My guide was carrying food and cooking utensils in her backpack, and we were going to settle down and have lunch when it started pouring with rain. It had been sunny in the morning, so this came as a surprise.

I opened my umbrella and we took shelter under it, but after a few minutes my guide said that this rain didn’t look like it would stop soon, and we should try and make our way back. This turned out to be an ordeal. The trees offered only some protection from the rain, and the mud track that we had taken on the way there had become really slippery.

The steep bits of the path were perilous under the rain. I had to crawl up and down on all fours, finding roots and branches that I could grab in case my feet slipped, while being careful not to grab anything with thorns. A few times we both slipped and got cuts on our hands, but luckily we managed not to hurt ourselves badly.

After what seemed like hours we got back to the proper path, and we found a simple shelter that someone had made there, with a log to sit on and a canvas to protect us from the rain. My guide cooked some rice and fish, and we ate while the rain poured on around us.

It finally stopped raining, and we walked back down the path. We were approaching the village, and I felt that we were over the worst, when we got to the scariest part of all. There was a river that you had to cross to get back to Kupa Kupa. In the morning it had been nothing more than a stream, and we crossed by walking on the rocks. But now, due to the rain, the river was swollen, and it was perhaps 5 or 6 metres across.

There was no other way to get back to the village. No bridges, no roads, no anything. We either waited overnight for the flooding to subside, or we crossed. The guide said we would have to wade through the river, with the water up to our waist. This didn’t seem too terrible a prospect, since we were soaked anyway. When she tried to cross however, she realised that the current in the middle of the river was incredibly strong, because the water was coming all the way down from the mountain.

The current was fierce enough to sweep us off our feet, and probably drown us, if we tried to wade to the other side with nothing to hold on to. Luckily my guide knew what to do. She cut down a long pole of bamboo with her knife, and threw the pole across the river until it was firmly caught in the shrubs on the other bank. Then she fastened it to our bank with some rocks. We would have to cross the river holding on to the bamboo cane, so the current wouldn’t sweep us away.

I was dubious. Would the bamboo hold? I could also see that once we reached the other bank, which was very steep, we couldn’t just get out of the river. We would still have to wade in the water for a few metres, holding on to the shrubs so the current wouldn’t sweep us away, until we reached the entrance to the path.

My guide seemed confident however, and she crossed first, still carrying her enormous backpack. After some nudging I found the courage to follow. The current in the middle of the river was frighteningly strong, but holding on to the pole I could still stay on my feet. Once we got to the other bank the current was weaker, and it was easy enough to reach the path.

I had never tried to wade through a swollen river before, and didn’t realise how strong the currents can be. Now I understand why people drown in floods. The whole experience of trekking back under the rain was scary and uncomfortable, but it also gave me an appreciation of what it means to be at the mercy of Mother Nature in the middle of a rainforest.

After wading the river, we finally reached Kupa-Kupa. We had to walk through the village to reach the scooter. The local people, seeing me and my guide looking drenched, kept asking what had happened. She gave the same reply about 50 times, in a mix of the local language and Indonesian. After hearing her say “hello” in the Tobelo language dozens of times, in what sounded a lot like a tonal language, I repeated the word in the same tones to some kids who had greeted me with a “hello mister”. Everyone fell around laughing.

Perhaps impressed by my attempt to speak her language, my host/guide invited me to join her at a wedding party in the village that evening. The reception was held outdoors, under a large tent to protect people from the rain. I was, of course, the only white person, and I attracted much attention. Local men kept offering me cigarettes and glasses of arak. There was a lot of “Dari mana? Italia? Valentino Rossi!”.

People’s clothing was mostly informal, so I didn’t feel out of place in my sandals and t-shirt. A couple of invitees looked quite drunk. Although this was mainly a Christian community, I did spot a couple of women in hijabs amongst the crowd. There was music blasting from loudspeakers, and the young people kept getting up and dancing in big groups. The way they danced was interesting, with everyone circling the room in the same direction, moving to the beat.

The following day I rested and recovered from the trip, and planned my return to Bali. Perhaps it was the trek in the jungle under the rain, or two weeks without a hot shower, but the idea of going back was starting to feel attractive.

All the airports in the area are tiny and have limited flights. I finally decided to go to Morotai, an island just North of Halmahera, and fly back from there. I would have to fly to Ternate, then to Makassar, and finally to Bali, but there was no way of getting to Bali in less than three flights.

The speedboat from Tobelo to Morotai took an hour and a half, plus an hour of hanging around at the harbour until it filled up with passengers. Public transport in Eastern Indonesia is like this; there are no fixed times, it’s just a matter of waiting until the boat or bus has filled up.

Morotai is a small island, whose major distinction is that it was the site of a massive battle between the Allies and the Japanese in 1944. The island hosted the last stranded soldier of the Japanese army who refused to surrender after the end of the war. Teruo Nakamura held out in the jungle for decades, until his hut was accidentally discovered by a pilot in 1974, after which the Indonesian army organized a search mission and arrested him. He was then repatriated to Taiwan, since he was not in fact Japanese, but a Taiwanese aborigine conscripted into the imperial Japanese army.

I stayed in Morotai for one night, and only saw the main town of Daruba. The people of Morotai are originally from Halmahera and speak the same languages. The town still has some relics from the war, including some American tanks and armoured vehicles which are kept on public display.

Daruba looked small and sleepy, but somewhat more orderly and pleasant than Tobelo, and at least the mobile phone signal was strong here. The homestay where I spent the night had nice rooms with wifi, but only basic toilets and showers in outdoor sheds with no sink and, of course, no hot water.

I rented a scooter and went to a beach in town to try snorkelling, but when I sat on the beach I was surrounded by curious local boys. They were respectful enough, but it made it hard to relax. Soon two adult men arrived, shooed away the children and tried to have a conversation with me in Indonesian. It then started pouring with rain, and I had to rush back on my scooter under the rain. Sudden thunderstorms are a constant in the Moluccas, and you will end up caught in one every now and again.

After a night on the island, the next morning I took a becak for the ten-minute ride to Morotai’s tiny airport, one of the smallest I’ve seen. The security check is done as you enter the building, and then you check-in at the only counter and go to the only waiting room, with nothing at all in the way of shops or refreshments. I flew on a small propeller plane to Ternate, and then on to Makassar and finally back to Bali.