As those who know me will attest, I have a fondness for travelling to places that have interesting histories and are off the beaten path of world tourism. The two volcanic islands of Ternate and Tidore, in the Moluccas, certainly fit the bill.

For centuries, these two small islands were the world’s major producers of cloves. This put them at the centre of the global spice trade, in the days when spices were both scarce and precious. Essentially they were a bit like Kuwait or Brunei today, small but possessing a valuable resource that the world wanted.

In the 14th century the islands started interacting with Chinese and Arab traders, and by the 15th century the rulers had converted to Islam, followed by the population at large. The islands turned into rival sultanates and became regional powers, extending their rule to other parts of Nusantara (the Indonesian archipelago).

Ternate’s sultanate was always the mightiest of the two. By the end of the 16th century, it ruled over an area including parts of the much larger islands of Sulawesi, Mindanao (now in the Philippines) and even Papua. But by this point the European powers were taking over the spice trade, and the Portuguese established a presence in Ternate. They were eventually kicked out, but the Spanish and then finally the Dutch followed.

The Dutch wanted to concentrate the growing of spices on a few islands that they controlled, and they forced both Ternate and Tidore to eradicate much of their clove production (while paying them compensation), reducing their wealth and influence.

By the 19th century the spice trade had become less important anyway, and the two islands faded into obscurity. After Dutch colonialism ended, they were incorporated into Indonesia alongside the rest of the Moluccas. The Moluccas are known as Maluku in Indonesian, but in the West many still remember them as the fabled “Spice Islands” of old lore.

Today the Moluccan islands are divided into two provinces, North Maluku and Maluku, which include over 1000 islands and 3 million people. They are one of Indonesia’s most geographically remote and least developed areas, sitting between Sulawesi and the vast wilderness of Papua. The region is not well connected, and most of the islands can only be reached by ferry. There is little tourism, and few people ever end up there.

Ternate and Tidore are now part of the province of North Maluku. Ternate is still the most developed of the two islands. It has about 200,000 people, and its main town is the biggest and liveliest in the whole province. It’s not huge, but by regional standards it is a veritable metropolis. It also has the region’s main airport.

To get to Ternate from Bali I had to transit through Makassar, in Sulawesi. As my plane approached Ternate from the South, I could see a scattering of islands from the window. Most of them looked like the oceanic islands you see in cartoons, with a mountain (often a volcano) covered in green vegetation sitting in the middle, and a few modest settlements along the coast.

Ternate also has a volcano in the middle, but the Eastern side is covered in houses and urban sprawl, as I could already see from the plane. I had booked a room in Kurnia Homestay, in the middle of the town, where many of the (few) foreign travellers to the island tend to stay. The owner’s neighbour came to pick me up at Ternate’s small airport.

The homestay’s owner, Aty, spoke good English and my room was nice, although just like everywhere I stayed in the region the bathrooms had no hot water, which is seen as a luxury. Apart from me there was a Japanese girl staying there, brought to these parts by her professional interest in spices. She may well have been the only other foreign traveler on the island.

Ternate’s main town looked to me like other small towns I’ve seen around Indonesia. The place is very clearly Muslim, with mosques at every corner and most women donning hijabs. I even saw quite a few women wearing the full Arab-style face covering, with only the eyes left visible.

Typically for Indonesia, walking around the town was not particularly pleasant due to the lack of continuous, usable sidewalks. While the streets did not look particularly prosperous, the town has plenty of commercial activity going on and even a big modern mall on the seafront, housing the only cinema in North Maluku province.

It is rare for foreign travellers to visit Ternate, and I attracted surprised stares and attention everywhere. Youngsters and children often cried out “mister”, the Indonesian term of address for a Westerner, when they saw me pass, or tried to engage me in conversation.

Gojek drivers and others would ask me where I came from, and then compliment my poor Indonesian as sudah lancar (already fluent). When they heard I was from Italy their reaction was, more often than not, to say the name of Valentino Rossi, the motorcycle racer. Almost all the men I encountered in Maluku reacted this way at the mention of Italy. Motorcycle racing is apparently very popular in Indonesia. If I said I came from Rome, they would move on to Francesco Totti.

Many locals also asked in surprise how I even thought of going somewhere as out-of-the way as Ternate. I would reply that I like going to places with few people. I spoke far more Indonesian in a few days in Ternate than I did the entire previous month in Bali, where the locals tend to know English much better than I know Indonesian.

Ternate’s main town has a scattering of sites, including several forts left behind by the European colonial powers and the palace of the Sultan. The sultanate still exists, and while it does not have any official status nowadays (only the Sultan of Yogyakarta is still invested with real political power in Indonesia), it is clearly still an influential institution.

It is traditionally believed that the Sultan of Ternate protects the island from the volcano erupting. Fealty to the sultanate is particularly strong in the rural north of the island, where most of the sultan’s guards come from. During the communal riots and unrest that shook the Moluccas at the end of the nineties, the Sultans of Ternate and Tidore and their guards played important and disputed roles.

On my first day in town, I decided to go and visit the sultan’s palace. The palace was built in 1813, and it sits on a hill overlooking the sea. There is a museum which is supposed to have some rather interesting displays, including gifts from the King of Saudi Arabia and other potentates, but when I arrived it was closed. It should have been open in the middle of the day on a weekday, but it was not. The guidebook mentioned that the museum is often closed when it shouldn’t be.

Disappointed, I left and got a Grab motorbike-taxi to go back to my homestay. The driver asked me if I had been to the museum, and I said it was closed. He said “oh well, in any case the sultan in the palace is palso, false. Would you like to meet the real sultan?”. This sounded intriguing. I said “sure”. He stopped and made a call, then said that the “real” sultan would be happy to meet a guest from Italy.

I was not sure what I was getting myself into, but I agreed to let him take me to meet this mysterious person. The driver took me to a café by the sea. There was a middle-aged man with a moustache sitting at a table overlooking the ocean. He was apparently the “real” sultan. He could speak good English, and he was jovial and chatty.

Slowly, I understood that the person I was talking to was the half-brother of the current sultan, whom he considers to be a usurper. Apparently the old sultan, who died in 2015, had three wives. Two were local women and one, this man’s mother, came from Yemen, which explained his somewhat Arab features. The “false” sultan who now sat on the throne was the son of one of the other wives.

I googled it, and it seems that there was indeed a struggle over succession after the death of the old sultan. At one point, a crowd gathered outside the palace in support of the man who I met and his claim to the sultanate. Clearly my taxi driver happened to be one of his sympathisers.

The wannabe sultan told me he had grown up in Jakarta and had been an airplane pilot for many years. He showed me photos of his three kids, one of whom is also now a pilot. As we sat at the café, various men stopped to chat with him. Some of them had Muslim beards and round caps, and they greeted each other with “Assalamu Aleykum”.

At one point, the man started complaining to me about how the Moluccas, although rich in resources, remain poor while the Indonesian government pours all the money into Java. I know there is resentment against the Java-centric nature of Indonesia in the poorer East of the country, but this was the first time I heard someone express it directly.

He them went on to complain about the Chinese companies that run mining operations in Halmahera, the much larger island that sits right next to Ternate and Tidore. At this point the “real sultan” told me something shocking: some years ago, “his men” killed three Chinese miners in Halmahera out of resentment of the Chinese mining company, which never employed locals.

He claimed that in the aftermath, he was invited to Shanghai with a delegation to discuss the situation, and they had agreed on a deal by which at least 40% of the Chinese mining company’s employees would be locals. I searched on Google but found no information about these events, and I don’t know what to make of the man’s claims.

After a while, the sultan’s brother decided to take me on a small trip around the island’s coast with his car. Speaking to this lone European traveler who had ended up on his island was clearly entertaining him. As he drove around, he would regularly stop and greet people he knew. We drove north of the town and past the airport, and the views of the sea on the one side and the volcano on the other were quite impressive. Finally, he dropped me off at my homestay.

The next day I decided to go to Sulamadaha beach, on the northern side of the island. I took a Gojek for the half-hour ride. I read in the guidebook that the beach gets crowded with locals in the weekend. I went on a Saturday, but when I arrived at noon there was literally no one there, except for the owners of a row of depressing little restaurants with no customers.

The black-sand beach looked very nice, but it offered no protection at all from the blazing tropical sun. I saw a little path snaking around the coast and decided to walk on a bit. I followed the path, and after a while I reached an inlet known as Sulamadaha Bay. There were a few little restaurants on wooden platforms suspended above the water, and some locals swimming and snorkelling.

The bay was a little piece of tropical paradise, with incredibly clear water and almost no people there to spoil it. I left my stuff at one of the restaurants, changed into my swim trunks and dipped into the water. Lying on the rocks under the shade of the trees, with the warm water bracing my feet and legs, for a while I felt like I could stay there forever.

There was a small group of youngsters from Ternate, perhaps around 20 years old, playing in the water near me. The girls were swimming fully clothed, one with a hijab on. I started bantering with them, in the best Indonesian I could muster. They were friendly but also surprised to see me. One of them later told me he’d never spoken to a foreigner before. At one point I swam close to one of the girls, and she started giggling and exclaimed “oh, your skin is so white and mine so dark!”.

My new friends spoke no English, but they did teach me a few words in the local language. Ternate, like Tidore, has a language of its own, which doesn’t belong to the Austronesian group like Indonesian and most languages of the region, but is instead related to the languages of Papua. They are, in fact, the only Papuan languages to have a written tradition, and they used to be written in the Arabic alphabet.

Apparently this is the result of an ancient migration from Papua, although most Ternateans don’t really have Papuans’ dark skin and Melanesian features, and culturally also have little in common with them. In recent times there has been a shift away from the Ternate language, especially among the young and in the urban part of the island, and it turned out my new friends only spoke the language a bit, but normally use the local dialect of Indonesian.

In any case, when it came time to leave the bay I could find no Grab or Gojek to go back, since I was out in the middle of nowhere, so the youngsters offered to give me a ride back into town on one of their scooters. They took me all the way to my homestay, in a gesture of kindness towards a stranded foreigner on their island.

As I mentioned, Ternate has several forts left behind by the European invaders. On my last day there I visited the one known as Fort Tolukko, a fortification built by the Portuguese in 1522 to dominate a rare coral-free landing point to the island.

The fort was initially built with the approval of the Sultan, who hoped the Portuguese could help him gain a military advantage over his rivals. However, the Portuguese soon began to interfere in local affairs and push for the Christianization of the Muslim kingdom. After a Sultan who defied them was killed by the Portuguese in 1570, the locals rebelled and kicked the Europeans out completely by 1575.

The fort was then occupied by the Sultan himself, and later it was taken over by the Spanish, the Dutch and even briefly by the British during their invasion of the Spice Islands in 1810. In 1864 the Dutch governor ordered the fort vacated and some parts demolished. It was restored in 1996 and turned into a tourist attraction.

When I went the grounds seemed well looked-after, but there was no entry fee and no other visitors around. The fort was small and built in a distinctly Iberian style, quite different from the Dutch forts you often find in Indonesia. The views of the sea and the island of Halmahera from on top of the fortifications were pretty dramatic.

It struck me that in China, a genuine European fort from the 16th century would be overrun with Chinese tourists, even if it was located somewhere fairly isolated. This is partly due to China’s huge population, of course, and its relative lack of original historical sites. But it also speaks to the strong culture of domestic tourism which has sprung up in China in the last twenty years, with plenty of Chinese going on long road trips through Western China or on package tours that take them to every nook and cranny of the country.

In Indonesia, this culture of domestic travel seems to be far less present. Of course, there are less people with a disposable income than in China, but I get the impression that even inhabitants of the big cities in Java with money to spend would rarely think of exploring the backwaters of their own huge country in this way, preferring perhaps to travel abroad.

This might also be why people in the Moluccas often seemed amazed I would even think of going there at all. In remote parts of China the locals may be surprised to see foreigners, but they don’t find the concept of tourists visiting them strange anymore. Every town and county will designate a few tourists attractions, even when the basis for them is flimsy, and do its best to attract (Chinese) visitors. On the other hand, Ternate has some genuine historical sites and idyllic beaches, and it isn’t that hard to reach, but there is virtually no tourism to speak of, either foreign or Indonesian.

After spending several days in Ternate I decided to go and see its old nemesis, Tidore. The two islands are very close; it only takes seven minutes by speedboat to get from one to the other. Tidore is similar in size to Ternate, and it also has a volcano in the middle, but otherwise it feels very different.

Tidore has always lived in the shadow of its neighbour, and even now it has less people (120,000) and is much quieter and less developed. While Ternate gets migrants from other islands, Tidore sees few outsiders. The coast of the island is dotted by brightly painted wooden homes bordered by flower gardens and shaded by palm trees. The main settlements feel like overgrown villages.

The homestay where I slept had decent conditions, although still no hot water. The staff seemed oddly indifferent to my presence at first (they warmed up later), but out on the streets it was another matter. If people were surprised to see me walking around in urbane Ternate, they were even more surprised in Tidore. The port town of Goto, where I stayed, had a run-down main street with a few shops and restaurants. Strangers constantly stopped and said hello to me. The local restaurants looked dingy and uninviting, but I ate in several and the fish and chicken-based dishes turned out to taste very good.

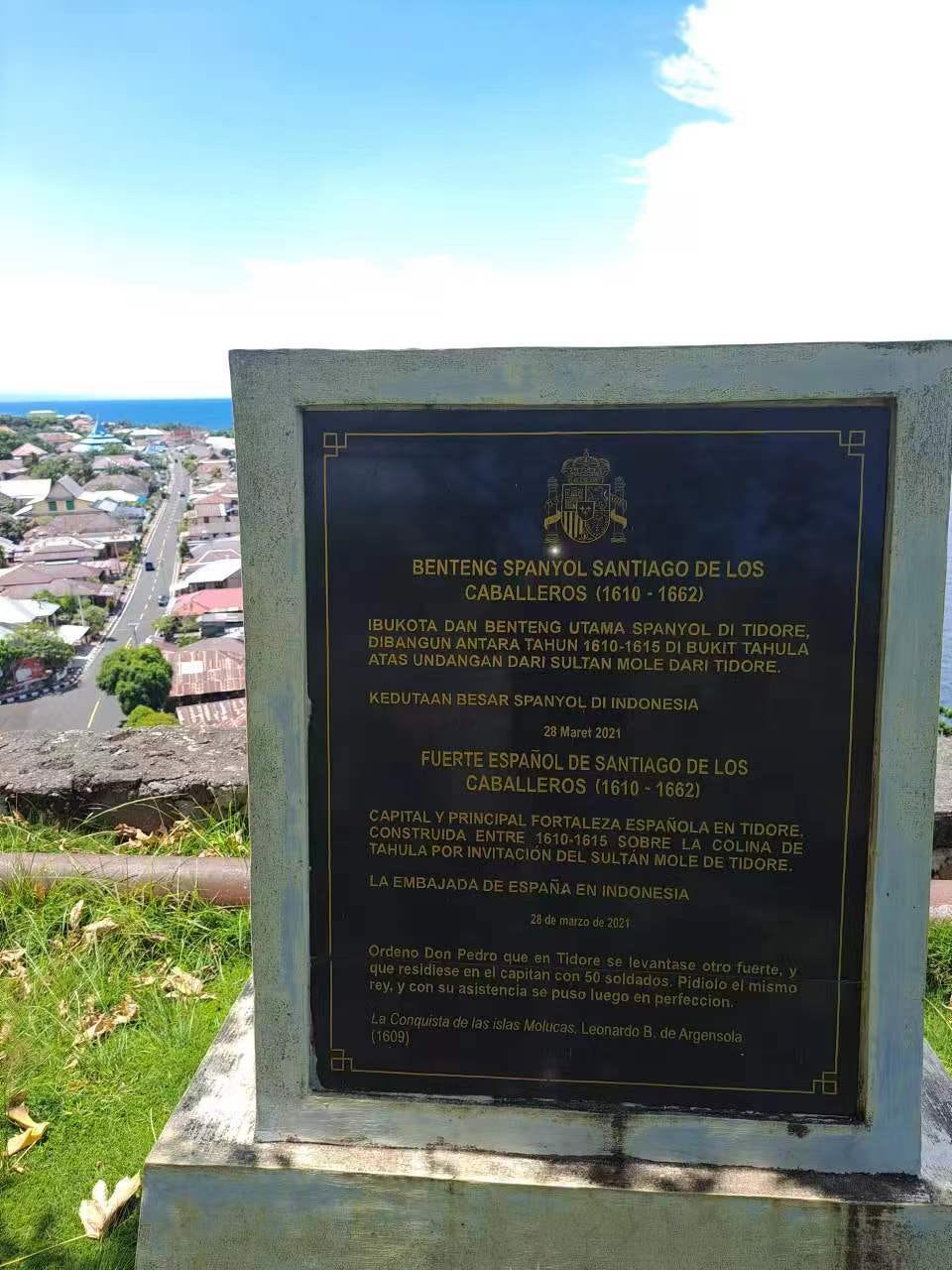

I rented a scooter to get around the island. I didn’t dare do this in Ternate, because driving in Indonesian cities makes me nervous, but there is so little traffic in Tidore that it felt safer. I went to see the two European forts left on the island, Fort Tahula and Fort Torre, both built by the Spanish and very close to each other. Particularly Fort Tahula, situated on a hilltop overlooking the sea, was impressively large, well-preserved and had spectacular views from the battlements. Once again, there was no entrance fee or other visitors.

I then went to the Sultan’s palace and saw a large group of men in military uniform training on the grounds. They were friendly and said I could come in and look around. The yellow flag of the sultanate, which displays Arabic writing including the Muslim shahada (there is no god but Allah and Mohammed is his prophet), flew alongside the Indonesian flag outside the palace.

Further down the hill there was a museum on the Sultanate. I was fully expecting it to be closed, but it was open, and there were two friendly women in hijabs working there. According to the guestbook, I was guest number 6 since the start of 2023! The previous five visitors had been four Indonesians and one Swiss who somehow ended up on the island in January. There was again no entrance fee, and quite a few interesting displays of traditional clothing and replicas of adat houses. Captions were only in Indonesian.

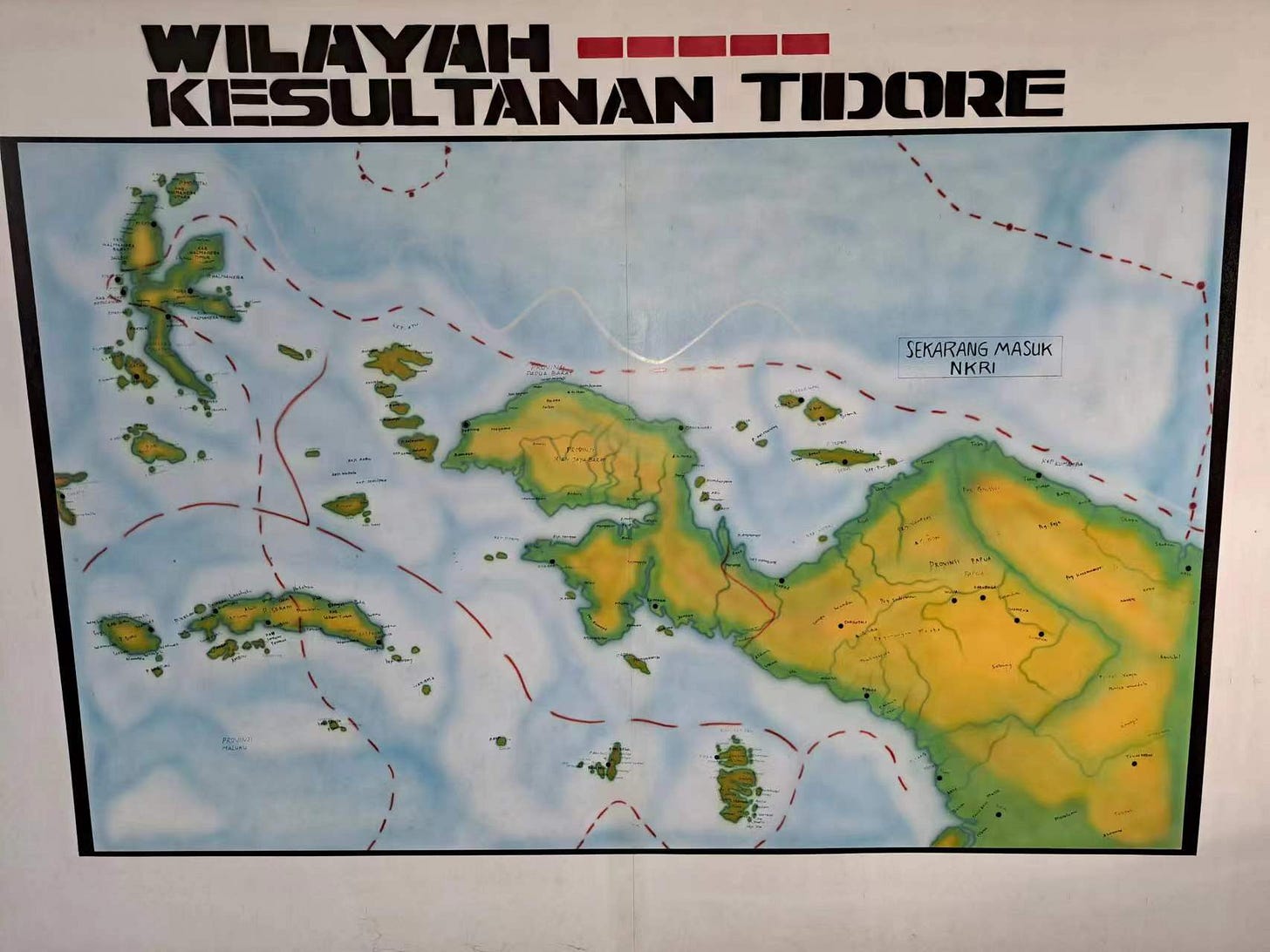

A map on the wall proudly displayed the sultanate’s maximum territorial reach, which included islands across the Moluccas and parts of Timor and Papua. The sultanate has a long and colourful history, but after the 26th sultan died in 1967 the institution was allowed to lapse, since the Indonesian government had no interest in keeping the old hereditary rulers around.

However, after Suharto’s rule ended in 1997 there was a push to revive local traditions, and a new sultan was enthroned. He was a direct descendant of Sultan Nuku of Tidore, who led a successful rebellion against the Dutch in the 18th century (with British help) and is now commemorated as a national hero of Indonesia. That sultan died in 2012, and his son now succeeds him.

After seeing the museum, I tried riding my scooter up the side of the volcano to reach the village of Gurabunga, at 600 meters of altitude, from which it is possible to organise hikes all the way to the crater. The road up the mountain soon became extremely steep, and as I got past a certain altitude the weather became drizzly and wet. The road was slippery, and my little scooter was having huge trouble making it up the steep hill. At some point I became worried about the safety of going any further, so I decided to give up and drive back down again.

I then drove to a place where Lonely Planet indicated I would find the island’s only white-sand beach, but I found absolutely nothing worthy of being called a beach there. Defeated, I stopped at a little shop to buy a drink. Outside the shop there were a few plastic chairs and a table overlooking the sea, and I sat and chatted a bit in my best Indonesian with the amazed shopkeeper, a disabled man on crutches who asked me what my religion was and how much it might cost to fly from Indonesia to Italy.

Once I got back to my homestay it started pouring with rain. I relaxed a while on the porch, and planned the next step of my trip, to the neighbouring island of Halmahera.